When development constricts our moral circle

You’ve probably heard the idea that as humans become more rational, they expand their moral circle: from caring mainly about family, to including friends, strangers, animals, and eventually even distant future generations. This story, often traced to thinkers like Peter Singer, is appealing. But how does it apply to growing up? As children mature into adolescents and develop greater rationality and moral reflectiveness, do they also become more just and more inclusive?

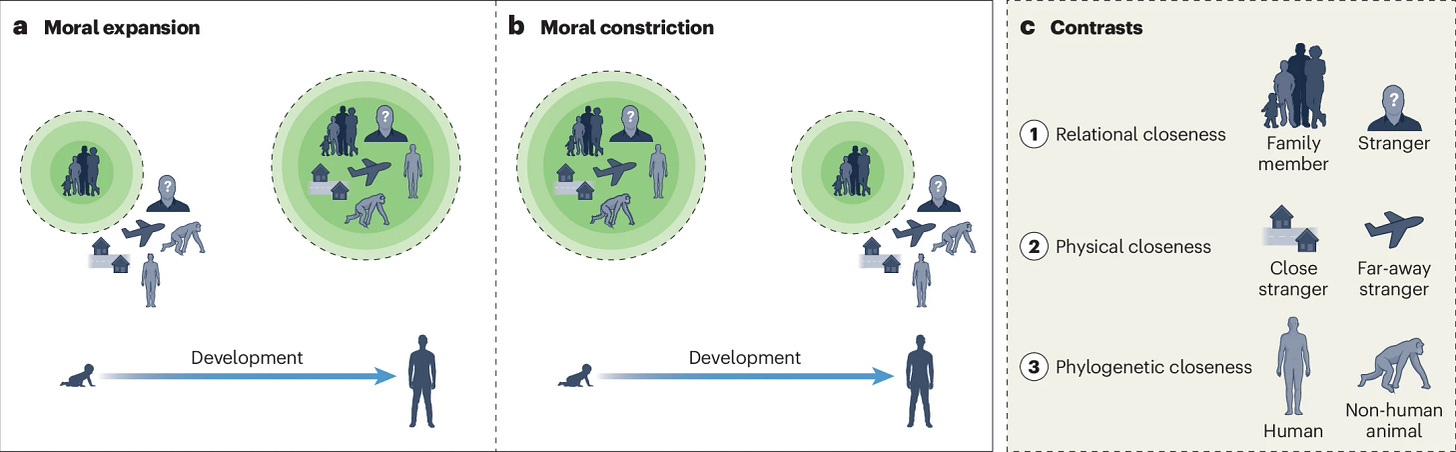

Our new paper, co-authored with Julia Marshall, Matti Wilks, and Karri Neldner and published in Nature Human Behaviour, shows that in some important domains, young children seem to start out more inclusive than older children and adults. That is, moral development doesn’t always mean moral expansion. Sometimes, it means moral constriction.

🔗 Read the full paper: doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02212-7

What we found

We reviewed evidence across three domains:

Relational distance (family vs. strangers)

Physical distance (nearby vs. faraway people)

Phylogenetic distance (humans vs. animals)

Across each of these contrasts, younger children (typically between 5 and 7 years old) were more likely than older children and adults to judge that distant others deserve help.

Some striking examples:

Young children often say that strangers have a moral duty to help someone in need, even more strongly than adults.

They’re more likely to think people should share resources with faraway children, not just local ones.

When asked about distributing food or toys, younger kids often favor equal distribution, even across large distances, whereas older children may favor those closer to them.

In moral dilemmas, children are more willing than adults to sacrifice one human to save multiple animals (e.g., 10 pigs or dogs).

Young kids also judge harm to animals more harshly than older kids do, even when the harm is socially normalized, like in farming.

In studies with cross-cultural samples, this pattern of early inclusiveness holds in both Western and non-Western settings.

This suggests that young children often begin with a broad and inclusive moral outlook, which becomes narrower over time.

Why does moral concern narrow with age?

We don’t know for sure, but we explore a few possible explanations:

Social learning: As kids grow, they absorb social norms about who “deserves” care, like prioritizing family, human beings, or ingroup members.

Cognitive development: Older kids better understand trade-offs and resource constraints, which may lead them to prioritize more narrowly.

Cultural values: In individualistic cultures, children may adopt norms emphasizing personal autonomy. In collectivistic cultures, they may be socialized to prioritize loyalty to close others and ingroup members.

Why this matters

These findings challenge the common idea that morality naturally progresses from selfishness to universal compassion.

Maybe we are not born morally narrow. Maybe we are born with a surprisingly inclusive capacity to care, and over time, we learn to direct that concern more selectively.

If that is true, then moral education should not only be about expanding the circle. It should also be about preserving and nurturing the broad concern children already show for distant others.

This could have implications for how we teach ethics, how we think about animal welfare, and how we foster concern for global issues like poverty and existential risk.

That said, much of this is still speculative, and to me, it feels somewhat counterintuitive. I say that because I still believe that rational reasoning, combined with empathy, can lead people to expand their moral circles. Think of the drowning child argument or philosophical arguments against speciesism. It appears that the real story is more complex.

My colleagues and I might be wrong in how we’re interpreting these findings, and we’d welcome counterarguments, alternative perspectives, or new evidence. Let us know what you think.

Fascinating work. I wonder, though: although children are highly caring *in theory*, they are commonly selfish if they have to, for example, give up a prized toy to another child, or otherwise subordinate their wants to those of others. So mightn't their greater moral concern be a function of powerlessness--that they rarely face the compromises that moral decisions demand? This might also explain why the most strident activists are often young, then become far less willing to take moral stands in middle-age when they’d have to pay for others' welfare...

Tom Rachman has a couple of good points, and 1 viable hypothesis. What say you, Lucius?